This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. For ORT, which had been training and educating Jews in the Pale of Settlement since its founding in St Petersburg in 1880, any opportunities the revolution presented came, ultimately, at an appalling cost.

The disappearance and untimely death of Jacob Tsegelnitski is a reminder of this human tragedy.

Jacob Tsegelnitski, a member of the World ORT Union Central Board, occupied the post of plenipotentiary representative of the WOU in Soviet Russia from 1923 until his arrest on false charges in 1938.

Born in what was then Vilna in 1886, Mr Tsegelnitski’s organisational skills and knowledge of agriculture propelled him quickly up the ORT hierarchy. At the tender age of 28 he became the first executive of ORT’s Relief through Work department and supervised ORT’s network of labour bureaus.

After the Revolution, he saved many residents of Petrograd from starvation through the horticultural cooperatives he helped to organise in the city’s outskirts. In 1923, he arrived in Moscow as chief representative of the World ORT Union in the new Soviet state.

“Tsegelnitski was never interested in the ongoing debate within ORT about cooperation with the Bolsheviks and preferred to focus on serving the broadest interests of the Jewish masses. He felt that it was his personal responsibility to do the best he could for Russia’s Jews, who in the fallout of the civil war were facing a humanitarian crisis,” wrote Alexander Ivanov, research fellow at the Interdepartmental Centre Petersburg Judaica of the European University in St Petersburg.

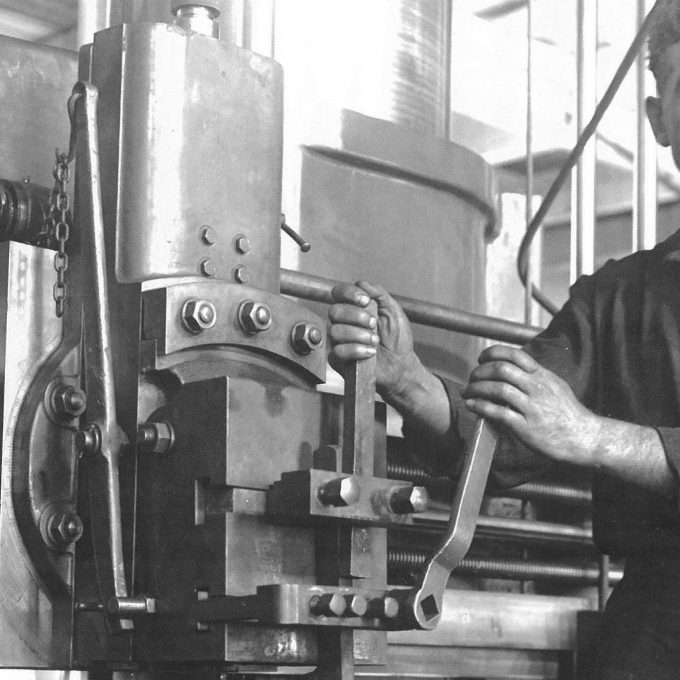

ORT took a leading role in raising the skills level of Jewish agricultural workers, organising vocational classes, and providing material support for professional schools and courses for industrial workers and craftsmen.

A highly successful initiative was to help people in the West to donate machinery and tools direct to Jews who were not recognised by the Soviet authorities as “productive” and, therefore, not entitled to full civil rights. Thousands of families benefited – often Shabbat observant, whose religious principles prevented them from working in factories. They now had the means to work at home or join cooperative enterprises and so regain their civil rights.

Later, Tsegelnitski championed the development of Birobidzhan as an autonomous Jewish region, in particular promoting it as a safe haven for Jewish refugees from Nazism. When it was officially established, in May 1934, it was hailed by the foreign pro-Soviet Jewish press as one of the greatest events in Jewish history. “It certainly brought hope, albeit short-lived, to many European Jews suffering from antisemitism and economic hardship,” wrote Ivanov.

ORT fundraising resulted in the establishment of factories and workshops and organised foreign resettlement in the region – mostly highly qualified agriculturalists, construction and electricity engineers and artisans who had graduated from ORT’s professional schools and colleges from central and western Europe.

The hopes raised by the Jewish Autonomous Region of Birobidzhan proved to be illusory but already ORT’s achievements had long been viewed with suspicion by Communist Party activists. They had complained to the Leningrad education authorities that the city’s Jewish professional school was organised by ORT, “a society subsidised by wealthy Jews from London, Berlin and New York. So even though the school is located in Soviet Russia, its real owner is the foreign bourgeoisie… We must urgently wrest the school from the influence of the bourgeois ORT.”

By the mid-1930s, ORT’s work was becoming increasingly difficult as Stalin’s terror gripped the country and in May 1938 the formal cooperation agreement between it and the Soviet organisation KOMZET expired.

Tsegelnitski started to wind down ORT’s presence but on 10 April, 1938, he was arrested by agent of the NKVD, the precursor of the KGB. By the end of the year ORT terminated its activities in the USSR but the leadership abroad tried desperately to intervene with the authorities on Tsegelnitski’s behalf. Despite their efforts, Tsegelnitski was found guilty of espionage and criminal activity in September 1939 and sentenced to five years imprisonment.

Records show that he died in the notorious gulag of Unzhlag, some 550 km east of Moscow, in February 1942.

In August 1957, four years after Stalin’s death, a Moscow military tribunal found there to be no evidence against Tsegelnitski and rescinded the guilty verdict. But ORT did not return to the land of its birth until 1990. It now has a dynamic educational network across the Former Soviet Unionserving more than 27,000 people every year.